Many people still use SHA-1 hashes and after 20 years of use, somebody finally figured out how to create collisions. Its time to move to SHA 256. The original post from the google security blog can be found HERE.

Cryptographic hash functions like SHA-1 are a cryptographer’s swiss army knife. You’ll find that hashes play a role in browser security, managing code repositories, or even just detecting duplicate files in storage. Hash functions compress large amounts of data into a small message digest. As a cryptographic requirement for wide-spread use, finding two messages that lead to the same digest should be computationally infeasible. Over time however, this requirement can fail due to attacks on the mathematical underpinnings of hash functions or to increases in computational power.

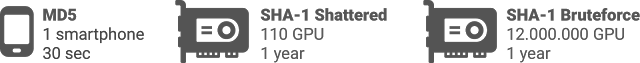

Today, more than 20 years after of SHA-1 was first introduced, we are announcing the first practical technique for generating a collision. This represents the culmination of two years of research that sprung from a collaboration between the CWI Institute in Amsterdam and Google. We’ve summarized how we went about generating a collision below. As a proof of the attack, we are releasing two PDFs that have identical SHA-1 hashes but different content.

For the tech community, our findings emphasize the necessity of sunsetting SHA-1 usage. Google has advocated the deprecation of SHA-1 for many years, particularly when it comes to signing TLS certificates. As early as 2014, the Chrome team announced that they would gradually phase out using SHA-1. We hope our practical attack on SHA-1 will cement that the protocol should no longer be considered secure.

We hope that our practical attack against SHA-1 will finally convince the industry that it is urgent to move to safer alternatives such as SHA-256.

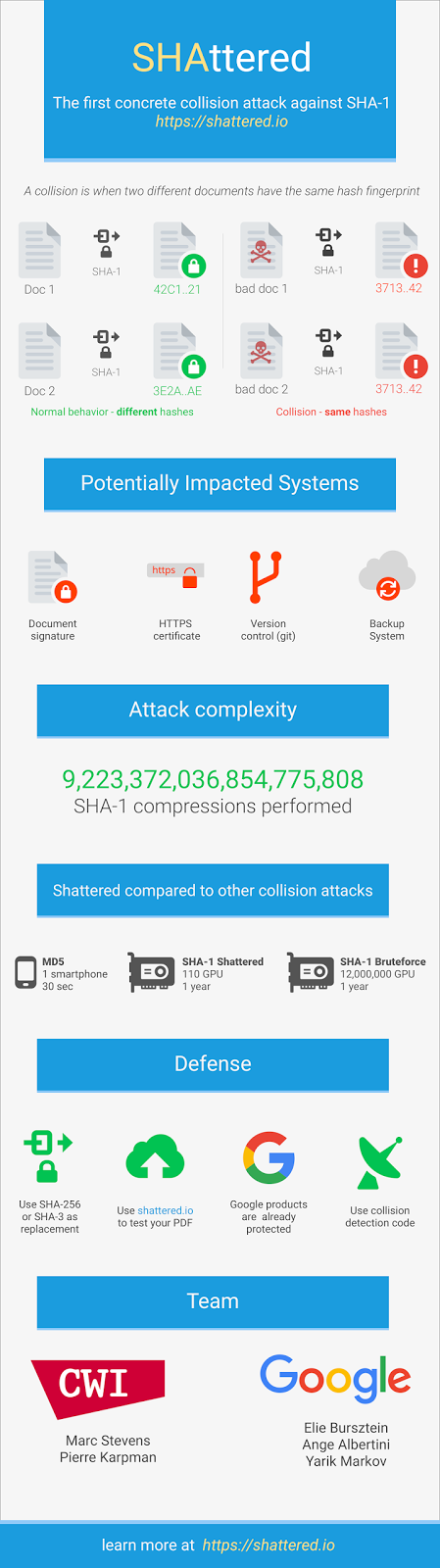

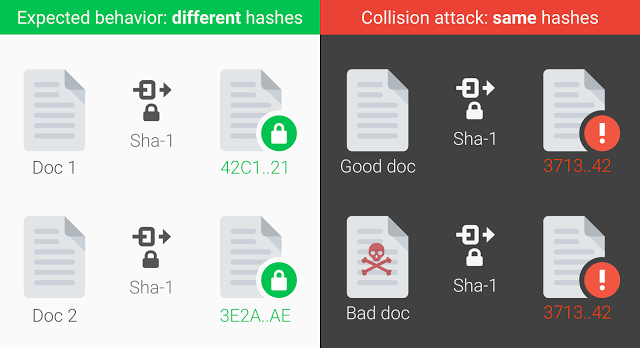

What is a cryptographic hash collision?

A collision occurs when two distinct pieces of data—a document, a binary, or a website’s certificate—hash to the same digest as shown above. In practice, collisions should never occur for secure hash functions. However if the hash algorithm has some flaws, as SHA-1 does, a well-funded attacker can craft a collision. The attacker could then use this collision to deceive systems that rely on hashes into accepting a malicious file in place of its benign counterpart. For example, two insurance contracts with drastically different terms.

A collision occurs when two distinct pieces of data—a document, a binary, or a website’s certificate—hash to the same digest as shown above. In practice, collisions should never occur for secure hash functions. However if the hash algorithm has some flaws, as SHA-1 does, a well-funded attacker can craft a collision. The attacker could then use this collision to deceive systems that rely on hashes into accepting a malicious file in place of its benign counterpart. For example, two insurance contracts with drastically different terms.

Finding the SHA-1 collision

In 2013, Marc Stevens published a paper that outlined a theoretical approach to create a SHA-1 collision. We started by creating a PDF prefix specifically crafted to allow us to generate two documents with arbitrary distinct visual contents, but that would hash to the same SHA-1 digest. In building this theoretical attack in practice we had to overcome some new challenges. We then leveraged Google’s technical expertise and cloud infrastructure to compute the collision which is one of the largest computations ever completed.

Here are some numbers that give a sense of how large scale this computation was:

- Nine quintillion (9,223,372,036,854,775,808) SHA1 computations in total

- 6,500 years of CPU computation to complete the attack first phase

- 110 years of GPU computation to complete the second phase