Cisco Talos provided a write up of research on a very interesting malware family they are calling Astaroth. The key items of interest are how it evades detection, the ability to remain targeted on systems within Brazil, and the use of YouTube channels. It’s a good read to understand how threats like this can adjust their tactics even if you are not located in Brazil. This should be a warning that a similar threat can be knocking on your door in the near future.

The original post can be found HERE.

- Cisco Talos is detailing an information stealer, Astaroth, that has been targeting Brazil with a variety of lures, including COVID-19 for the past nine to 12 months.

- Complex maze of obfuscation and anti-analysis/evasion techniques implemented by Astaroth inhibit both detection and analysis of the malware family.

- Creative use of YouTube channel descriptions for encoded and encrypted command and control communications (C2) implemented by Astaroth.

What’s new?

- Astaroth implements a robust series of anti-analysis/evasion techniques, among the most thorough we’ve seen recently.

- Astaroth is effective at evading detection and ensuring, with reasonable certainty, that it is only being installed on systems in Brazil and not on sandboxes and researchers systems.

- Novel use of YouTube channels for C2 helps evade detection, by leveraging a commonly used service on commonly used ports.

How did it work?

- The user receives an email message that has an effective lure, in this campaign all emails were in Portuguese and targeted Brazilian users.

- The user clicks a link in the email, which directs the user to an actor owned server

- Initial payload (ZIP file with LNK file) downloaded from Google infrastructure.

- Multiple tiers of obfuscation implemented before LoLBins (ExtExport/Bitsadmin) used to further infection.

- Extensive anti-analysis/evasion checks done before Astaroth payload delivered.

- Encoded and encrypted C2 domains pulled from YouTube channel descriptions.

So what?

- Astaroth is another example of the level of sophistication crimeware is consistently achieving.

- This level of anti-analysis/evasion should be noted, as the likelihood of this spreading beyond just Brazil is high.

- Organizations need to be prepared for these evasive and effective information stealers and prepared to defend against the sophisticated attack.

- Another example of how most adversaries are using COVID-19 themed campaigns to increase effectiveness.

Executive summary

The threat landscape is littered with various malware families being delivered in a constant wave to enterprises and individuals alike. The majority of these threats have one thing in common: money. Many of these threats generate revenue for financially motivated adversaries by granting access to data stored on end systems that can be monetized in various ways. To maximize profits, some malware authors and/or malware distributors go to extreme lengths to evade detection, specifically to avoid automated analysis environments and malware analysts that may be debugging them. The Astaroth campaigns we are detailing today are a textbook example of these sorts of evasion techniques in practice.

The threat actors behind these campaigns were so concerned with evasion they didn’t include just one or two anti-analysis checks, but dozens of checks, including those rarely seen in most commodity malware. This type of campaign highlights the level of sophistication that some financially motivated actors have achieved in the past few years. This campaign exclusively targeted Brazil, and featured lures designed specifically to tailor to Brazilian citizens, including COVID-19 and Cadastro de Pessoas Físicas status. Beyond that, the dropper used sophisticated techniques and many layers of obfuscation and evasion before even delivering the final malicious payload. There’s another series of checks once the payload is delivered to ensure, with reasonable certainty, that the payload was only executed on systems located in Brazil and not that of a researcher or some other piece of security technology, most notably sandboxes. Beyond that, this malware uses novel techniques for command and control updates via YouTube, and a plethora of other techniques and methods, both new and old.

This blog will provide our deep analysis of the Astaroth malware family and detail a series of campaigns we’ve observed over the past nine to 12 months. This will include a detailed walkthrough of deobfuscating the attack from the initial spam message, to the dropper mechanisms, and finally to all the evasion techniques astaroth has implemented. The goal is to give researchers the tools and knowledge to be able to analyze this in their own environments. This malware is as elusive as it gets and will likely continue to be a headache for both users and defenders for the foreseeable future. This will be especially true if its targeting moves outside of South America and Brazil.

Technical details

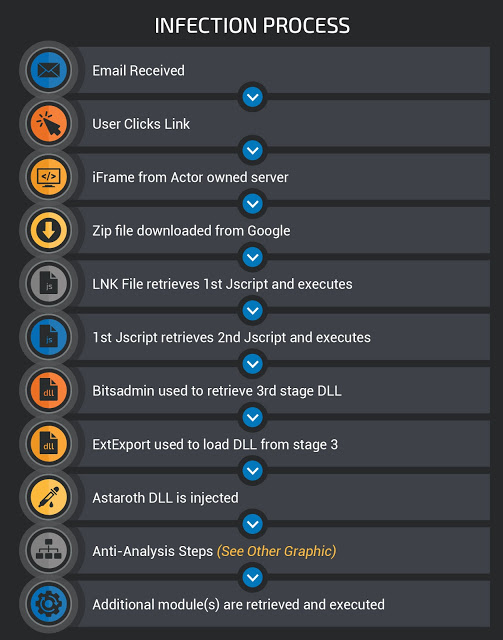

Astaroth features a multi-stage infection process that is used to retrieve and execute the malware. At a high level, the infection process is as follows. We will describe each step of the process in greater detail in later sections.

Delivery stage

These campaigns typically start with a malicious email. During our analysis, we have observed thousands of emails associated with campaigns attempting to spread Astaroth starting in mid-2019. The overwhelming majority of these email campaigns appear to be specifically targeting Brazil, and as such are written in Portuguese. Over the last six to eight months, these actors have leveraged a variety of different campaigns touching on several different topics. One of the more common examples is seen below.

This particular campaign was trying to get users to click a link purporting to be an overdue invoice — a common tactic for adversaries. The hyperlink in the email actually points to a different URL than what’s shown to the user. The user may think they are clicking a link to a car rental website local to Brazil, however, the link the user is actually clicking is below:

hxxp://wer371ioy8[.]winningeleven3[.]re/CSVS00A1V53I0QH9KUH87UNC03A1S/Arquivo.2809.PDF

One characteristic of the early campaigns was the use of actor owned domains along with subdomains (i.e. wer371ioy8 from above). We have seen a high volume of unique subdomains and URLs indicating with a high likelihood that the URL is generated randomly and the server is designed to respond accordingly.

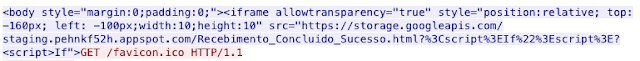

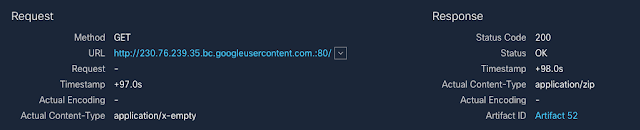

When we began to trace the infection, we saw where the malware actually resides. When a user clicks the link, they are redirected to Google Drive to download the actual malicious ZIP file that will be analyzed in later sections. There are lots of ways that adversaries are doing web redirection and we see techniques like 302-cushioning commonly. However, these actors instead used a tactic we used to see in the past — iframes.

Notice that this iframe makes use of relative positioning and renders the iframe above and to the left of the screen, something we commonly observed with exploit kits. This initial redirection into Google infrastructure also introduces SSL into the infection path, encrypting the intermediary requests. This traffic results in a clear-text request to a ZIP file hosted by Google, as shown below.

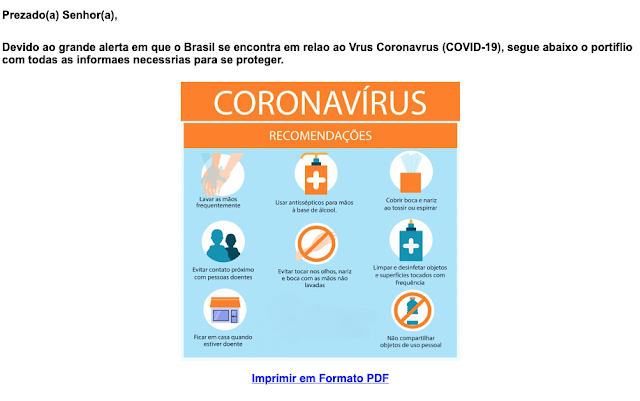

There were a couple of other interesting lures that these actors have leveraged during these campaigns, including COVID-19. In the email shown below the actors sent messages masquerading to be the Ministry of Health for Brazil. This is the group that provides updates to citizens regarding what’s being done to combat the COVID-19 outbreak.

CONTINUE READING BY GOING TO https://blog.talosintelligence.com/2020/05/astaroth-analysis.html or clicking HERE